Make Japan a Startup Nation

How can government best encourage economic growth?

By Jesper Koll

If you had two minutes with the new prime minister, to give your best-shot advice on how to create a better economic future for Japan, what would you say? From a macro perspective, by far the best answer is: Do whatever you can to make Japan a startup nation.

But where does economic growth come from? Not from the stuff politicians and technocrats talk about most of the time—e.g., monetary, fiscal, or trade policy. And importantly, it doesn’t come from population growth. It comes from entrepreneurs.

Clear-Cut Correlation

History has confirmed again and again that we only get sustained economic growth when human ingenuity and ambition are allowed and encouraged, and people are empowered to start an enterprise and build their own business.

China long had one of the world’s highest rates of population growth, but it only started becoming an economic miracle when the Communist Party encouraged entrepreneurship and private business in the early 1980s.

More generally, the numbers speak for themselves. When you analyze the world’s 40 leading economies over the past 30 years, you find a clear-cut correlation between the percentage of entrepreneurs in the adult population and the sustainable growth of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). More entrepreneurs create higher sustainable growth. In fact, if you raise the number of entrepreneurs in the population by one percentage point, your potential GDP goes up by about half a percent.

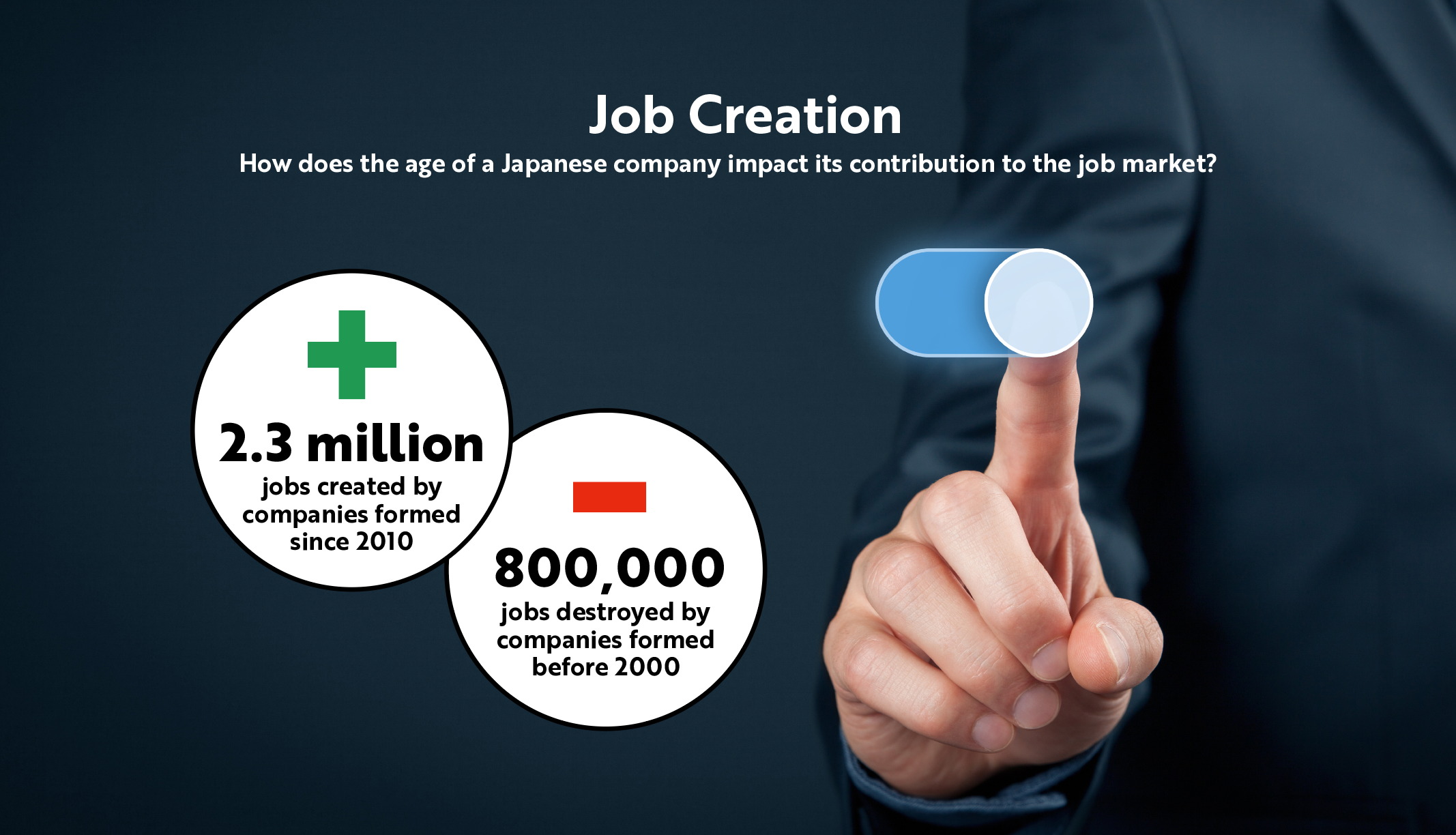

In even simpler terms, employment data confirms the positive power of entrepreneurship: startups have created 60–70 percent of new jobs in G7 countries over the past 20 years. Specifically, here in Japan, new companies set up after 2010 have provided about 2.3 million jobs over the past decade. In contrast, companies older than 20 years actually destroyed some 800,000 jobs over the same period.

So, dear prime minister, make no mistake—startups and entrepreneurship are a nation’s single most important source of growth and prosperity.

History has confirmed again and again that we only get sustained economic growth when human ingenuity and ambition are allowed and encouraged.

Finding Founders

The need for entrepreneurs is clear, but where do they come from?

Unfortunately, there is no magic bullet, no one simple policy tool that can be turned on to deliver entrepreneurs and create Startup Nation Japan. However, the key ingredients are all in place and, in my personal view, I firmly believe Japan stands at the brink of a golden age of entrepreneurs and startups.

Why? It’s a combination of cyclical and structural forces. Cyclically, the Covid-19 crisis has not only freed up resources but, more importantly, has become a catalyst for many people to rethink their career and life priorities. No matter how small, a startup can finally hire people and build teams, investing in what always yields the highest returns for any new venture: human capital. One of the biggest obstacles for growth and expansion has finally disappeared.

Even the most techy of tech companies, such as Google or Amazon, did not grow by the force of their superior algorithms, business models, or charismatic leadership vision. Instead, they grew as a result of the sweat equity and animal spirits of their team leaders, sales managers, and back-office clerks who pulled all-nighters. Elon Musk’s biggest problem is not tech, engineering, or digital transformation; it is his teams, the people who actually get stuff done.

In Japan, the bar for startups to attract talent has always been especially high because top graduates strongly prefer established companies. Bigger is supposedly safer. Here again, the current recession may well mark an important turning point. Not a week goes by that we don’t read about establishment companies announcing a restructuring plan. All of a sudden, big-company job security is not what it used to be. This is great news for entrepreneurs.

To be specific, I have the good fortune of working as an adviser and angel investor for a couple of Japanese venture capital funds. Over the past six months, all the startups with which we deal have grown their staff and partners. Several have more than doubled the size of their teams. Most importantly, the quality of potential candidates has grown enormously.

One young woman from a top establishment company, who has had no overseas or global experience, told me: “Working at my current employer has been great, but now that I know how good I am, and what I want, staying there puts me at risk. I don’t want to be reassigned to some random project by some random salaryman superior. I want to create my own destiny. Your startup is the best place to do that.”

To be sure, this young woman almost certainly is exceptional, and it may very well be wrong to present her as anything like the new norm for Japanese employees. However, unlike five or 10 years ago, candidates such as her do exist, and it would be wrong to underestimate the powerful ambitions—and awareness of opportunities—that Japan’s young talents and employees are prepared to explore.

Taking the leap from exploring to actually quitting one’s job and beginning a new career at a startup venture is likely to become easier. There’s no doubt that opportunities will increase, large established companies will continue to stagnate, and more young startups will demonstrate high, sustainable growth. Opportunities worth watching include:

Healthcare and biotech

Professional services and process automation

Education and deep tech-based materials

Anything serving wealthy Japanese retirees

Some will make a fortune building the Louis Vuitton retirement communities of Japan.

Learning from the Masters

On the structural side, Japan has developed a true and sustainable ecosystem of support for startups and aspiring entrepreneurs. Not a day goes by that the major newspapers don’t advertise a startup competition or venture capital symposium. Even Keidanren—the Japan Business Federation, which is the proud sanctuary of Japan’s corporate culture—now fully embraces innovation and entrepreneurship in its strategic vision. Japan’s elite establishment now knows that BAU—business as usual—is no longer an option.

Most importantly, Japan has a new generation of successful entrepreneurs, people who have built true going concerns, who commercialized and monetized an original idea, who overcame many obstacles and difficulties to build their dream. Sure, they have money to invest; but more fundamentally, many of these new successful entrepreneurs are focused on creating a positive legacy by giving back, mentoring, and advising the next generation.

Hidden from view by media obsession with Silicon Valley superstars, Tokyo, Osaka, and Fukuoka have become hotbeds of private initiatives to grow and develop a startup culture. These include mentorship programs, incubators, accelerators, venture capital funds, and daily discussions on the drop-in audio chat app Clubhouse. This private-sector ecosystem of open discussion, sharing, and networking is vital because a sustainable startup culture can only develop if success is celebrated and, more importantly, if failure is peer-encouraged to become a catalyst for another try.

As Japan’s most successful entrepreneur, Yanai Tadashi, founder of FastRetailing, which owns Uniqlo, supposedly once said, “I failed about 25 times before I finally succeeded.”

All said, the new Japanese golden age for entrepreneurs is very exciting. If I am right, we will have to become more optimistic about the overall outlook for Japan. Because one thing is certain: private entrepreneurship—not government handouts—will build future prosperity.

Dear prime minister, I trust you understand.

Jesper Koll

Global ambassador

Monex Group Inc.

THE ACCJ JOURNAL

Vol. 58 Issue 7

A flagship publication of The American Chamber of Commerce in Japan (ACCJ), The ACCJ Journal is a business magazine with a 58-year history.

Christopher Bryan Jones,

Publisher and editor-in-chief

Advertising & Content Partnerships